Its findings will be issued in a report that may include what the panel believes caused the incident; whether there was any act of misconduct, negligence or violation of law; and safety recommendations that could prevent future calamities involving submersibles.

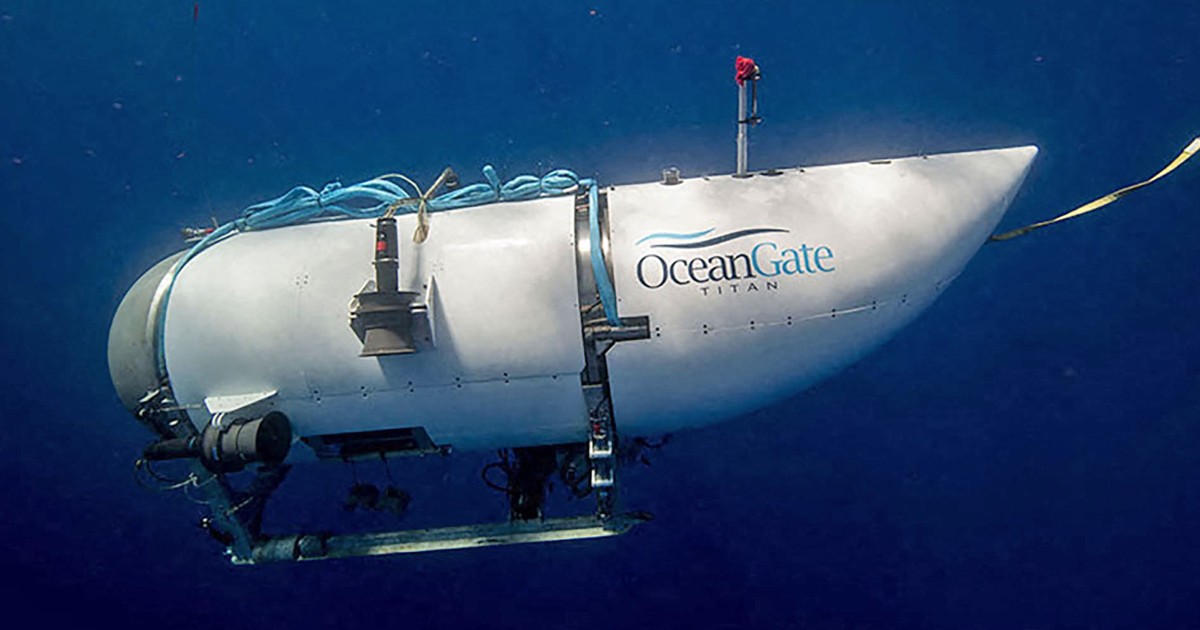

The hearing in South Carolina included former employees and executives of OceanGate, the Washington state-based operator of the Titan, some speaking publicly for the first time, as well as industry experts who sought to piece together the culture of the company, its business plan and the run-up to the fatal dive.

Those on board were OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, 61, who was piloting the Titan; deep sea explorer Paul-Henri Nargeolet, 77, who was experienced in visiting the Titanic wreck site; British tycoon Hamish Harding, 58; and Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood, 48, and his son, Suleman, 19.

Almost immediately, OceanGate came under heavy scrutiny as a result of the disaster, in part because it involved civilian passengers paying $250,000 apiece to go on the expedition, but also because fatal incidents involving submersibles — of which a handful are capable of diving as deep as the Titanic — are nearly unheard of.Here are key revelations that emerged from the Coast Guard’s hearing:

At the outset of the hearing, the Coast Guard released photos and video of the Titan’s tail cone resting on the bottom of the Atlantic near the Titanic’s bow.

While officials concluded in the initial investigation that the Titan was likely involved in a “catastrophic implosion” because the craft couldn’t handle the deep-sea water pressure, the discovery of the debris was what made them confident no one survived, they said.

The Coast Guard also revealed one of the last messages the Titan sent to its support ship before losing contact: “All good here.”

David Lochridge, the former marine operations director of OceanGate, testified that Rush was more concerned about profits and cost-cutting measures than in building a viable submersible.

“The whole idea behind the company was to make money,” said Lochridge, who joined OceanGate in early 2016 and was fired from his role after about two years. “There was very little in the way of science.”

Lochridge would go on to be locked in a legal battle with OceanGate, claiming he was fired because he complained about quality control.

Another former engineering executive, Tony Nissen, said he voiced concerns to Rush after the Titan’s original hull — made out of experimental carbon fiber, which has not been proven to repeatedly withstand deep-sea pressures — was compromised after it was struck by lightning during a test mission in 2018. Nissen said he was fired after he refused to sign off on another test mission the following year and had even told Rush, “I’m not getting in it,” referring to the Titan.

Meanwhile, OceanGate’s former director of administration, Amber Bay, who joined the company in early 2019, testified that there were instances when the business couldn’t meet payroll, so Rush had to dip into his own money.

“He increased his investment by making a deposit, and we were able to meet payroll,” she said, adding that the financial situation was so pinched that employees were also asked to defer their paychecks.

OSHA accused of failing to review safety concerns in timely manner

In January 2018, following his firing at OceanGate, Lochridge said he filed a quality inspection report regarding the building of the Titan with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the federal agency that oversees workplace safety.

Upon Lochridge’s termination, OceanGate filed a lawsuit alleging breach of contract, claiming he violated terms of his contractual employment by discussing confidential information with other employees and OSHA representatives.

But instead of OSHA pressing ahead with his claims, he said the representatives only dragged their feet — allowing OceanGate to go unchecked as it designed and built the Titan.

“I believe that if OSHA had attempted to investigate the seriousness of the concerns I raised on multiple occasions, this tragedy may have been prevented,” Lochridge said.

An OSHA spokesperson said in a response to NBC News that the agency did forward his safety allegations to the Coast Guard, which has the jurisdiction to investigate such claims. The agency said it could review only his claims of employment retaliation, and that “the investigation followed the normal process and timeline for a retaliation case.”

Once Lochridge and OceanGate agreed to settle their litigation in late 2018, OSHA ended its investigation “pursuant to the terms of the parties’ agreement,” the spokesperson said.

Titan never inspected by industry organization

Roy Thomas, an engineer for the American Bureau of Shipping, testified that OceanGate never contacted the organization, which advises and verifies whether a marine vessel complies with industry standards.

Thomas said the choice of the main material for the hull, carbon fiber, which has long been used within the aerospace industry, is “susceptible to fatigue failure” in deep-sea pressure settings. Submersible hulls typically use titanium; carbon fiber is also costlier.

Thomas added that the organization would never have classified the Titan based on the materials used. The Coast Guard also noted at the start of the hearing that the Titan never underwent an independent review, which is standard practice in the industry.

Titan malfunctioned just days before doomed final dive

The Titan suffered more than 100 equipment issues in the two years before the June 2023 implosion, including losing its forward dome during a test dive in 2021 and a mechanical failure that same year during an expedition to the Titanic. That trip had to be aborted.

The Titan also malfunctioned days before the implosion, marine scientist Steven Ross testified.Rush was piloting a trip with Ross and others on board. At one point, an issue with the Titan’s buoyancy caused the platform to shift and the passengers were left to “tumble about,” Ross said. No one was hurt, but it took an hour to get out of the water during such a distressing incident, he added.

“One passenger was hanging upside down,” Ross said. “The others managed to wedge themselves into the bow end cap.”

Exact cause of implosion may be ‘indeterminate’

Expert testimony from Bart Kemper of Kemper Engineering Services gave preliminary findings for what may have caused the disaster.

Among the possibilities, he said, are breakage of the carbon fiber hull, a manufacturing failure related to the hull or an issue with the acrylic window.

Ultimately, “the root cause for the implosion is indeterminate at this time,” Kemper said.

Earlier in the hearing, OceanGate co-founder Guillermo Söhnlein, who left the company a decade before the Titan disaster but continued to champion Rush’s efforts, said a cause for the implosion may never be known.“I don’t know who made what decision when and based on what information,” he told the hearing panel. “And honestly, I don’t know if any of us will ever know this, despite all of your team’s investigative efforts.”

OceanGate CEO had cavalier attitude: ‘No one is dying’

Witnesses who knew Rush painted a picture of a businessman who strove for innovation in creating a new type of submersible, but also refused to slow down.

Matthew McCoy, a former OceanGate operations technician, testified about a “tense” meeting with Rush in 2017 about what the CEO said he would do if he came under regulatory scrutiny at a U.S. port.

“If the Coast Guard became a problem, then he would buy himself a congressman and make it go away,” McCoy said, adding that he resigned soon after.

William Kohnen, the CEO and founder of submersible maker Hydrospace Group, said he spoke to Rush in 2018 about the direction of OceanGate as peers in the industry took notice of what he was doing.

Rush “said the usual response that ‘it takes too long,’” Kohnen testified about getting OceanGate’s submersible classified by the industry. “‘It’s too expensive and they don’t know about this technology. I don’t have time to explain my technology.’”

That same year, Lochridge had confronted Rush about his safety concerns before he was fired. In a transcript of the conversation made public by the Coast Guard as part of the hearing, Rush denied he was going to put anyone at risk with the Titan.

“Everything I’ve done on this project is people telling me it won’t work — you can’t do that,” Rush said.

“I can come up with 50 reasons why we have to call it off and we fail as a company,” he added. “I’m not dying. No one is dying under my watch — period.”