Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey has said interest rate cuts could soon become “more aggressive”, sparking a drop in the value of the pound.

Speaking to The Guardian, Mr Bailey said the Bank may be able to become “more activist” in its approach to borrowing costs if recent positive inflation trends hold.

The comments mark a departure from his previous approach, when he said rates would only be lowered “gradually.” Shortly after that interview, the pound fell by nearly one per cent against the dollar and the euro.

The Bank cut rates from 5 per cent to 5.25 in August, the first reduction since March 2020, after inflation returned to the 2 per cent target. Although the figure has since risen back up to 2.2 per cent, experts have been forecasting another interest rate reduction before the end of the year.

The Bank is expected to cut rates next month by another quarter percentage point to 4.75 per cent, but Kathleen Brooks, research director at XTB, said that in light of Mr Bailey’s comments, financial markets also now see a 61% chance of another reduction in December.

“The market has used Mr Bailey’s comments as a green light to price in more monetary loosening,” she said.

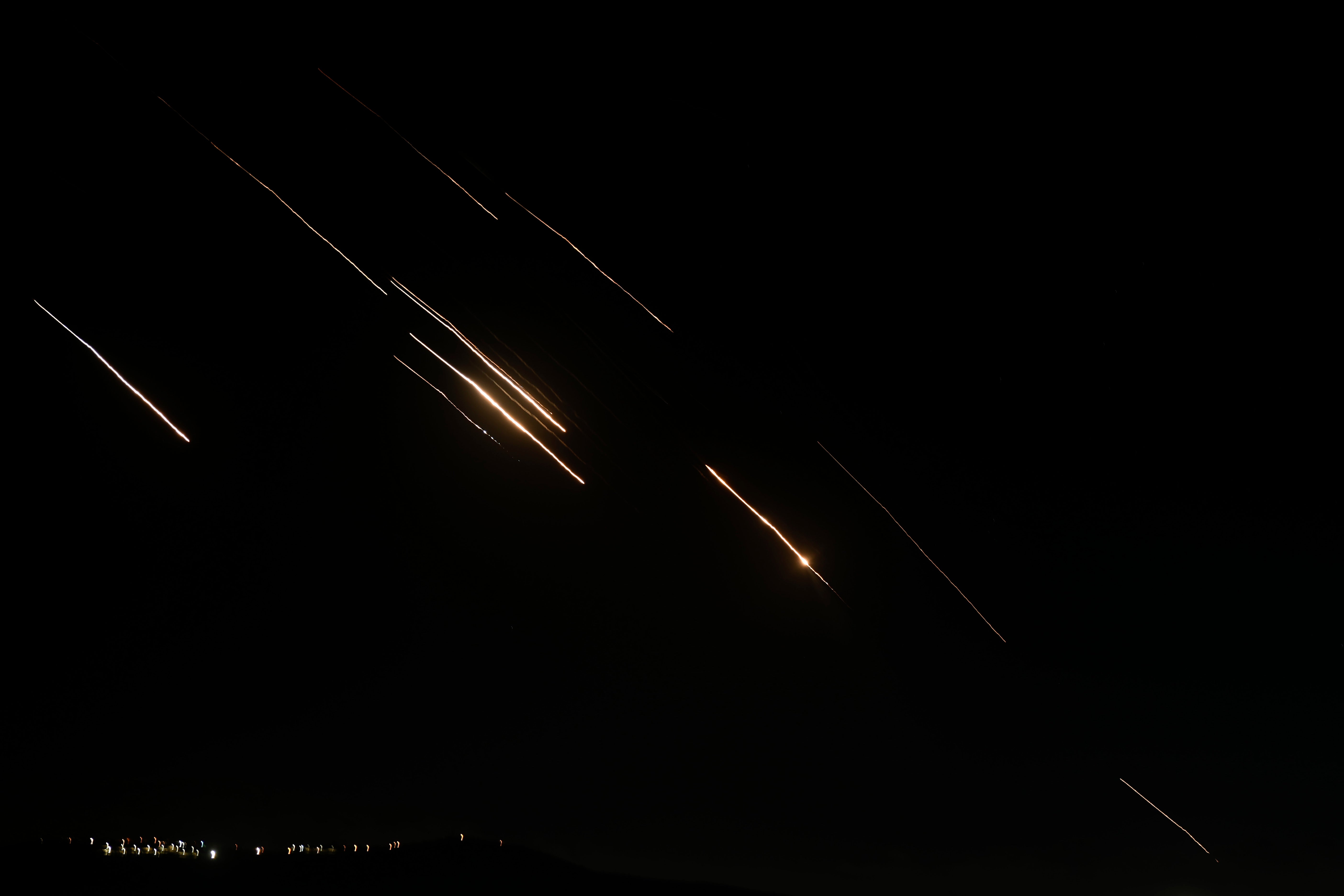

Mr Bailey also said that the Bank is monitoring developments in the Middle East “extremely closely” amid steep rises in the cost of oil, which surged this week after the Israeli invasion of southern Lebanon and Iran’s missile attack on Israel.

He said: “Geopolitical concerns are very serious,” adding: “It’s tragic what’s going on.

“There are obviously stresses and the real issue then is how they might interact with some still quite stretched markets in places.”

A report from the Bank’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC) on 2 October warned that global financial markets are vulnerable to shocks following a “spike in volatility” over the summer amid uncertainty over the geopolitical situation worldwide.

But Mr Bailey said oil prices have not seen the eye-watering increases of the past in the year since the Hamas attack on Israel.

He said: “From the point of view of monetary policy, it’s a big help we haven’t had to deal with a big increase in the oil price.

“But obviously we’ve had that experience in the past, and in the 1970s the oil price was a big part of the story.

“Obviously we keep watching it. We watch it extremely closely to see the impact of the latest news.”

He warned that, while markets remain stable, “there’s also recognition there’s a point beyond which that control could break down if things got really bad”.