“It used to be that if you made the median income, you could afford the median-priced house,” said Domonic Purviance, a housing expert at the Atlanta Federal Reserve. “That’s not the case anymore.”

When Haley and Ben Williams purchased their home Elkhart, Indiana, in December 2023 for $265,000, they accepted a challenging financial scenario. Their mortgage rate was 8.125% — above the roughly 7% national average at the time, which was hovering near 20-year highs. The couple estimated their monthly costs would include spending $176 on the principal and more than $2,000 on interest, taxes and insurance.

“We went for a house we knew would be difficult moving forward,” Ben said, but they felt it was a “needed sacrifice.” “We have our son and are looking to expand our family,” he explained. And the alternative was continuing to live in a rental with a mold problem that cost $900 a month, a place Haley said they were “so desperate” to get out of.

Homes in their price range — which they’d hoped would top out at $250,000 — went fast and to cash buyers, the Williamses said. Elkhart is a city of around 60,000 people about two hours east of Chicago, where a household making the area’s average annual salary of $67,000 would use roughly 22% of its monthly income to pay for a median-priced home of about $240,000 as of August 2024. While that ratio is less than the cost-burdened 30% threshold, it has doubled in the area in just the last three years.

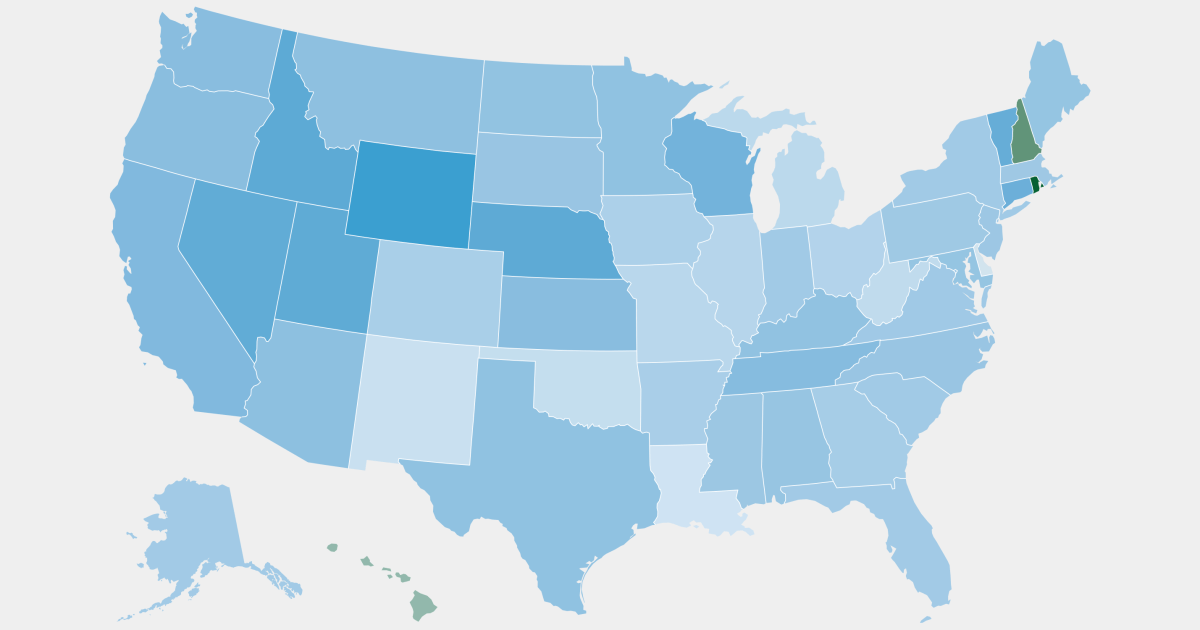

And Elkhart is no outlier. Today, in more than 30% of U.S. counties tracked by the NBC News Home Buyer Index, average-income house hunters presented with a median-priced home would end up in cost-burdened territory should they buy.

That reality has left many middle-class families sitting on the sidelines. Those households accounted for 49.7% of new homebuyers in 2022, down from 60.1% in 2010.

Daniel McCue, a senior research associate at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, said record home price growth was one driver of cost burdens, but also rising property taxes and insurance premiums. These have combined with high interest rates to create punishing pressure, even as many Americans are earning more money. From 2013 to 2023, the median annual household income in the U.S. has risen 50%, to $80,610.

But those pay gains largely haven’t kept up with housing-market conditions, said McCue. “All these costs are exposing who’s on the margins in terms of paying for their homes,” he said. “You look at households earning less than $30,000 a year — it was something like 95% of older adults were cost-burdened.”

He notes that single parents and Black, Hispanic and Native American households are also relatively more affected by cost burdens. “It’s attached to income inequality and wealth inequality, as well between household types and races and ethnicities,” he said.

Purviance, from the Atlanta Fed, said lower-income households and people on fixed incomes are also experiencing a disproportionate squeeze from housing costs: “They’re feeling inflation in their rents and homeownership and everything else.”

These pressures frequently require painful economizing elsewhere as families look to keep a roof over their heads. For example, McCue said, cost-burdened homeowners may struggle to keep up with home maintenance, leading to unhealthy or unsafe living environments. That could further erode a nationwide housing stock that, according to one paper from the Federal Reserve, already needs nearly $150 billion in repairs.

“You’re put into distress by any sudden increased costs. You don’t have the freedom to spend that money elsewhere,” said McCue.

Haley Williams said her family has been making it work, but it has entailed some cutbacks. “I’ve been a lot better at utilizing food to prevent waste and limiting the amount of meat we buy and cook because prices are so expensive,” she said.