Getty Images

Getty ImagesPeter Jay, the former economics editor of the BBC, has died aged 87.

At various times, Jay was also economics editor of the Times newspaper, presenter of ITV’s Weekend World, British Ambassador to Washington, launch chairman of TV-am and chief of staff to Robert Maxwell.

In a statement, his family said: “Peter Jay’s family are very sad to announce he died peacefully at home today 22 September aged 87.

“He was a much loved husband, father, grandfather, brother, uncle, cousin, friend, and colleague.”

Charming, brilliant and arrogant in equal measure, he was famously described at school as ‘the cleverest young man in England.”

“Is there someone cleverer in Wales?” came the retort.

Once tipped as a future world leader by Time magazine, Jay was later installed in splendour as Her Majesty’s Ambassador to the US.

But what went up, came crashing down.

His time in Washington was overshadowed by the public disintegration of his marriage. So spectacular was the scandal, it later inspired a Hollywood film.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJay was born on 7 February 1937, and enjoyed a glittering start to life.

His father, Douglas, was a Labour cabinet minister and destined for the Lords.

An early proponent of “modernisation” of the party, he argued for ditching its working class image and abandoning nationalisation as early as the 1960s.

His mother, Peggy, was a leading light of the London County Council and described by a local paper as the “uncrowned queen of Hampstead”.

He was educated at the Dragon School in Oxford before, like his father and grandfather before him, going on to Winchester.

There, he scooped a host of academic prizes and was, inevitably, made head boy.

After national service in the Royal Navy, his effortless rise continued at Christ Church, Oxford, where he graduated with a first class honours degree in politics, philosophy and economics

Getty Images

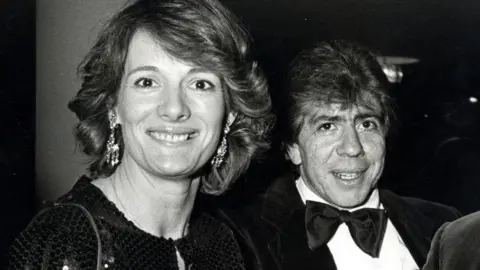

Getty ImagesIt was at Oxford that he met Margaret, daughter of the future Labour prime minister Jim Callaghan and the couple married in 1961.

Jay secured a job at the Treasury, before being appointed economics editor of the Times.

For a while, he was based in Washington where he became enthralled by the work of a new breed of free-market thinkers, including the Chicago-based economist, Milton Friedman.

Jay used his columns to promote “monetarism” in England. It later became Mrs Thatcher’s guiding economic philosophy but it also influenced his father-in-law.

He even said he wrote parts of Callaghan’s 1976 party conference speech.

“We used to think that you could spend your way out of a recession,” the prime minister told a sceptical audience. “I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe suffered fools badly, and saw his articles as part of a high-minded battle of ideas.

A sub editor once dared to complain that one piece was difficult to understand.

“I only wrote this for three people”, came the lofty reply, the editor of the Times, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Governor of the Bank of England.”

Jay attempted to follow his father into politics, but failed to be selected as the Labour candidate for Islington South West for the 1970 General Election.

So, he moved into television.

In the 1970s, he presented a news analysis programme called Weekend World for London Weekend Television where he became close friends with the programme’s creator, John Birt.

Together, they launched a savage critique of journalistic standards in TV.

Pictures, they complained, took precedence over analysis – and this “bias against understanding” could only be addressed by bringing in experts and putting them in front of camera.

Later, this “mission to explain” became a central feature of Birt’s time as director general of the BBC.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesJay might have remained a journalist but, in 1977, he was suddenly appointed as British Ambassador to Washington.

With no experience in politics or diplomacy, his appointment was met by furious accusations of nepotism.

James Callaghan faced angry questions in the House of Commons. But the decision had been the Foreign Secretary’s.

David Owen had felt the Jays would charm the incoming Carter administration and – by virtue of their personal friendship – Jay would be loyal in his service.

“Here comes Peter Jay,” was the headline in the Washington Post, “Britain’s brilliant and insufferable new ambassador”.

Jay and Margaret’s two years in Washington were a diplomatic success – but a personal disaster.

By the time an incoming Conservative government called time on Jay’s appointment, Margaret was having an affair with Watergate journalist, Carl Bernstein.

The breakdown of two marriages was immortalised as Heartburn – a thinly-disguised, autobiographical, tragi-comic novel by Bernstein’s wife, Nora Ephron.

It later became a Hollywood film starring Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson.

The scandals kept coming. Jay was reported to have fathered a son with Jane Tustian, their children’s nanny at the embassy.

The Daily Mail got wind of it, and – angry that he’d left her – Jane told them everything. Jay remained tight-lipped, until a blood test confirmed he was the father.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn his return from the US, Jay led the consortium that set up TV-am, which successfully bid for the ITV breakfast television franchise in December 1980.

The launch of the new TV station was beset by highly publicised problems.

He was forced to rush the new broadcaster to air just weeks after the BBC had first broadcast its own early morning TV offering.

The decision to make the new show highbrow and news-heavy was based on a mistaken belief that the BBC would do the same.

In the event, viewers were not ready for a heavyweight agenda over their cornflakes, much preferring the BBC’s lighter magazine style of programme.

TV-am’s viewing figures plunged, and pressure from investors led to a boardroom coup.

Jay was pushed out in March 1983. A fortnight later, to great fanfare, came the first appearance of Roland Rat.

Getty Images

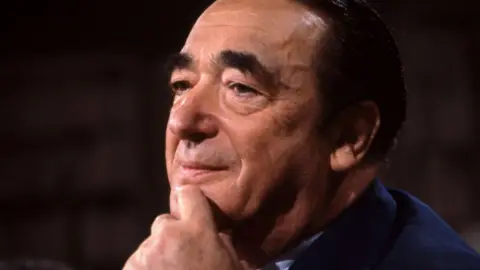

Getty ImagesIn 1986, Jay was announced as chief of staff to Robert Maxwell, the flamboyant and later disgraced press and media tycoon.

Maxwell loved calling him “Mr Ambassador”, but subjected him to a barrage of late night phone calls and a daily round of humiliation.

Jay stayed for three-and-a-half years, working for a man he later described as “barbarous” but insisting he managed to shield himself from lasting damage.

“I was surrounded by an invisible glass wall through which (Maxwell) could never penetrate. His manner never got under my skin,” he said.

In the end, an old friend came to the rescue in the shape of Birt, now the BBC’s director general.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring his decade as the broadcaster’s economics editor, Jay reserved his appearances for special occasions.

There was sniping in the press that he was hard to tempt away from his farmhouse in Oxford, where he lived with his second wife, Emma, and their three children.

The highlight of his time at the BBC came with Road to Riches, a landmark series which examined the economic history of mankind.

It gave him space to explore money, a subject that had always fascinated him.

“After sex, money is our second appetite” he once said, and freely admitted he’d gone into television to pay for luxuries, like his precious, private yachts.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesHis time at the BBC came to an end in 2001, around the time that Greg Dyke, an incoming director general, reviewed the way the broadcaster explained the economy to its audience.

After that, Jay spent time as a director of the Bank of England, lecturing and doing consulting work before fading gently into retirement

He once described his career as ending in anti-climax, having once been Ambassador to Washington.

But, more often, he presented it as “a chapter of accidents” and “a diverting and enjoyable ramble through life.”

But, no objective observer could describe such a life as a “ramble”.

It was a thrilling, exhausting, white-knuckle ride.